It was also a show defined by its funky, happy, black soul-inspired soundtrack and its multi-racial cast. In Schloss' view, its walking distance from Sesame Street to the Good Life Café, and from Check 1-2 back to 1 2 3 4 5 - 6 7 8 9 10 - 11 12.

Regardless of whether or not Schloss is "right," soul music is the fossil fuel of hip hop. But we've hit peak production. By the time Dilated Peoples started rocking, we had already over-exploited our American Soul reserves. These days, the blogosphere has pretty much leveled the digging playing field to the point where producers who don't know the difference between a 45 and a 78 now have access to the most esoteric CTI and Philly International "wax." Unless you are someone like Kanye West who can just pick something off the radio and clear the sample with a phone call, even if its something that came out last year, it is far more difficult to stay soulful and still be fresh.

In solving this dilemma, we should look to the Jackson brothers. But no, not those Jackson brothers. Otis and Mike Jackson, aka Madlib and Oh No, have released albums in the last few months which display what can only be described as Loop-Digger Imperialism. The most recent installment in the Beat Konducta series, a sort of Encyclopedia Madlibica, is a tribute to the music of India's film industry. Meanwhile, younger brother Oh No's arguably better effort, Dr. No's Oxperiment is, as his Myspace puts it, "an audio tour of Turkish, Lebanese, Greek and Italian Psych-Funk." Apparently in the 1960s and 70s, Americans weren't the only ones with groove and soul.

In fact, when one looks at the influence of hip-hop music in musical traditions globally it isn't difficult to imagine a world, 40 years ago perhaps, where musicians in Europe, Africa and the Middle East interpreted their musical heritage via American Soul and R&B, which was comparably popular at the time. It should logically follow that in exotic and obscure lands the world over, like untapped oil fields under an unsuspecting Persian Kingdom, are stacks of unheard loops, American Soul set to tabla and sitar.

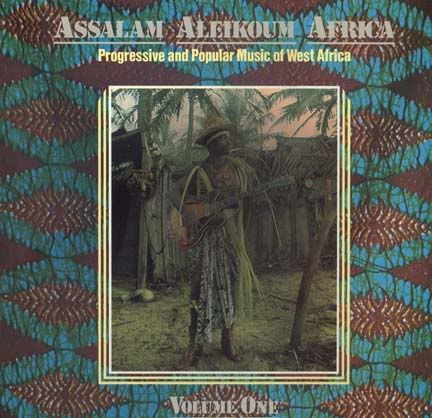

As much as I like this oil metaphor, my own contribution as a Loop-Digger Imperialist has to do with a different country raped by Europeans for a valuable resource: the Ivory Coast. About a year ago I picked up Assalam Aleikoum Africa: Vol. 1 from Gozi-Riya in Madison.

Released in 1976 on the Antilles label, Assalam Aleikoum Africa: Vol. 1 is basically the greatest hits of the Societé Ivoirienne du Disque, a long-dead record label based in Abidjan, the capitol of The Republic of the Ivory Coast. Even after its alleged independence from France in 1960, The Republic of the Ivory Coast was inundated with French coffee and cocoa traders (i.e., the sons of failed slave traders) even throughout the 70s. Large, cosmopolitan cities like Abidjan became cultural Meccas for West Africans, and the Societé Ivoirienne du Disque is one of the results. This combination of oppression, creativity and opportunity could just as easily describe Detroit or Muscle Shoals, and indeed the Societé was a contemporary of Gordy's Motown and Stewart & Axton's Stax.

And all historical trivia aside, Assalam Aleikoum Africa: Vol. 1 - from the Osibisa-esque title track to the Hendrix tribute - is primo.

Assalam Aleikoum Africa - Francis Kingsley & Emitais

I am, however, a Jealous Digger, and so that's all you'll get from me. I'm not going to zip the whole album up and send it out to be pillaged by the hip-hop world's French coffee traders. Can you dig it?